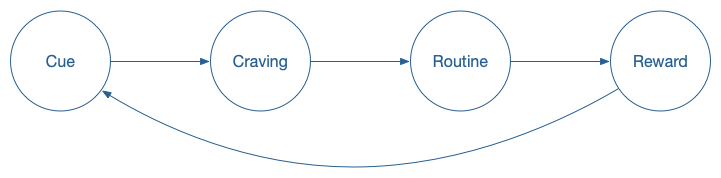

In Atomic Habits, James Clear lays out a four-phase cycle for habits: cue, craving, routine, reward. In response to a cue, or trigger, we have a craving. To satisfy the craving, we begin a routine. At the end of the routine, we receive the reward. If we enjoy the reward, our primitive lizard brain (the basal ganglia) learns the routine will satisfy the craving. It also starts to associate the routine and the with the cue.

You can see this at work with Pavlov’s famous dogs. Pavlov rang a bell before feeding, and before long, the dogs started drooling as soon as they heard the bell, whether or not it was time to eat. They had been conditioned to associate the cue (“I hear a bell”) with a craving (“I’m hungry”), a routine (“Let’s eat!”), and a reward (happy tummy).

I used to help people go through a stop-smoking program. Nicotine has a very short half-life; within a couple of hours, the body completely forgets what it is. Unlike some other addictions, there is no biological craving. It’s all psychological.

That blah feeling in your mouth an hour after you eat, finding a bit of food stuck in your teeth, feeling a lighter in your pocket, the smell of your clothes, the sight of an ashtray, arguing with someone, getting behind the wheel… they’re all cues that you’ve trained your lizard brain to follow up with a cigarette.

Fortunately, it’s not that hard to shuffle things around and avoid starting a bad habit loop entirely. For example, if someone we were helping would smoke after a meal, we’d have them finish their meal with a cold, refreshing glass of grapefruit juice, brush their teeth with a new brand of toothpaste, and rinse with cinnamon mouthwash.

Nobody’s lizard brain knows what to do with the lingering taste of grapefruit juice and cinnamon mouthwash. It’s a new sensation. There’s no association of “if I taste grapefruit and cinnamon, I can get a quick pick-me-up by lighting up”. It’s just not there. No cue, no craving, no cigarette.

Two things I want to point out here.

First, the earlier you intercept the behavior, the easier it is to change. At the top of the mountain, behavior is just a small stream, easily diverted. Further down, it’s still possible, but you have to deal with a larger river.

Second, when you divert a river, the river doesn’t cease to exist. The best way to break a bad habit is to replace it with a good habit. Your basal ganglia still has an After Dinner playlist—grapefruit juice and brushing your teeth. Your doctor and dentist will love you.

You can also upgrade habits from good to better. Find a habit you’d like to change, identify the cues at the headwaters, and adjust.

Starting with a known point (“When I finish eating…”). Connect it to a good habit (“…I will enjoy some grapefruit juice”). Then add another (“…and brush my teeth”) and another (“and use mouthwash”). This is called habit stacking. You can build large, healthy routines that happen automatically by stacking smaller habits together.

It all start with being aware of the cues that trigger your behavior. Unplug the bad habits that are holding you back and connect with the habits that will build the life you’re working towards.

Question: What habits would you like to upgrade? Share your thoughts in the comments, on Twitter, LinkedIn, or Facebook.